The Use of Ciclosporin in Cutaneous Cell-Poor Vasculitis

HISTORY AND CLINICAL EXAM

A 6-year-old, neutered, female, Labrador Retriever dog presented with an eighteen-month history of pinnal tip lesions. Initial symptoms included alopecia, scaling and palpable pinnal thickening. This progressed to crusting, linear ulceration and intermittent haemorrhage of the apex and concave surface of the pinnal tips. The tail tip had become necrotic prior to referral and a partial amputation had been performed with no histopathology assessment. No further tail lesions had occurred since. There was no history of drug administration prior to lesion onset. A relative of the dog (parent) had previously been diagnosed with vasculitis.

A 6-year-old, neutered, female, Labrador Retriever dog presented with an eighteen-month history of pinnal tip lesions. Initial symptoms included alopecia, scaling and palpable pinnal thickening. This progressed to crusting, linear ulceration and intermittent haemorrhage of the apex and concave surface of the pinnal tips. The tail tip had become necrotic prior to referral and a partial amputation had been performed with no histopathology assessment. No further tail lesions had occurred since. There was no history of drug administration prior to lesion onset. A relative of the dog (parent) had previously been diagnosed with vasculitis.

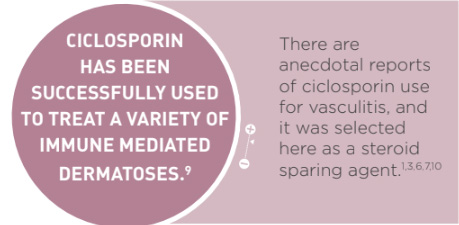

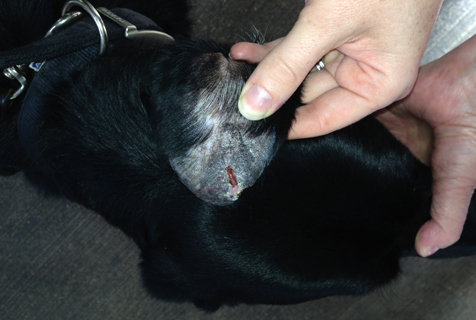

On presentation, general clinical examination was unremarkable and the dog was systemically well. Dermatological examination revealed lesions were isolated to the pinnal tips bilaterally. The right pinna was alopecic, hyperpigmented and palpably thickened, with the pinnal margin being moderately hyperkeratotic. The left pinna was similarly affected but also had adherent haemorrhagic crust on the pinnal margin adjacent to a 1.5cm linear ulcer and margin notch (see figure 1). Removal of the haemorrhagic crust revealed purulent discharge. Intermittent head shaking was noted and lesions were mildly painful to palpate.

DIFFERENTIALS

-

Cutaneous vasculitis / vasculopathy (including cell-poor vasculitis / ischaemic dermatopathy)

-

Proliferative thrombovascular necrosis of the pinnae

-

Lupus vasculitis

-

Cryopathy

DIAGNOSTICS

Cytology of the left pinnal margin lesion revealed neutrophils phagocytosing cocci bacteria. Cefalexin was administered at 25mg/kg BID PO for three weeks to treat this secondary infection prior to further diagnostics. As vasculitis was suspected, a biopsy was performed on the left ear margin and histopathology results were consistent with cell-poor vasculitis. Haematology, biochemistry and urinalysis were within normal limits. Coombs test, Anti-nuclear-antibody test and Cold Agglutinin antibody testing were negative.

TREATMENT

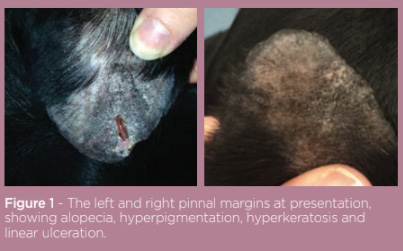

Prednisolone was administered at a gradually reducing dose regime starting at 1mg/kg BID PO for one week, then 1mg/kg SID for 10 days, then 1mg/kg every other day for 10 days, then 0.5mg/kg every other day. Six weeks on, re-examination showed lesion improvement with complete healing of the ulceration and crusting. Alopecia, fibrosis and hyperpigmentation remained. Propentofylline was added at a dose of 5mg/kg BID PO. Four months on, steroid side effects had become problematic to the dog and owner with polydipsia, polyuria and polyphagia being noted. Blood sampling for haematology and biochemistry was unremarkable. Attempts to reduce the prednisolone dose further resulted in relapse in ulceration and crusting of the pinnal margin (see figure 2). In order to reduce the dependence on steroid therapy, it was decided to add ciclosporin into the treatment regime at a dose of 5mg/kg SID PO. Concurrent Propentofylline was continued as before and the prednisolone dose was gradually reduced to 0.15mg/kg.

Prednisolone was administered at a gradually reducing dose regime starting at 1mg/kg BID PO for one week, then 1mg/kg SID for 10 days, then 1mg/kg every other day for 10 days, then 0.5mg/kg every other day. Six weeks on, re-examination showed lesion improvement with complete healing of the ulceration and crusting. Alopecia, fibrosis and hyperpigmentation remained. Propentofylline was added at a dose of 5mg/kg BID PO. Four months on, steroid side effects had become problematic to the dog and owner with polydipsia, polyuria and polyphagia being noted. Blood sampling for haematology and biochemistry was unremarkable. Attempts to reduce the prednisolone dose further resulted in relapse in ulceration and crusting of the pinnal margin (see figure 2). In order to reduce the dependence on steroid therapy, it was decided to add ciclosporin into the treatment regime at a dose of 5mg/kg SID PO. Concurrent Propentofylline was continued as before and the prednisolone dose was gradually reduced to 0.15mg/kg.

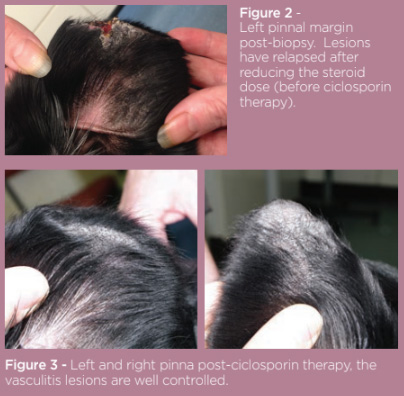

Re-evaluation six weeks into the new treatment regime revealed good control of the vasculitis symptoms. Hypertrichosis of the feet was noted but there were no problematic side effects. The prednisolone was withdrawn and the vasculitis remained controlled for a further 3 months of follow up.

DISCUSSION

Cutaneous vasculitis is an uncommon canine reaction pattern characterized by an inflammatory immune response, most commonly thought to be a type III hypersensitivity reaction, targeting blood vessels1,2,3. Underlying factors may include drugs, infectious disease, adverse food reactions, malignancy and immune-mediated diseases3,4 , although the majority of cases are considered to be idiopathic in nature despite extensive workup5.

Skin lesions are caused by inflammatory changes in cutaneous blood vessel walls causing disruption of adequate blood flow and oxygenation of tissue2,4. Clinical signs commonly include erythema, alopecia, ulcers, crusts, and sloughing of necrotic tissue4, that were all seen in this case. Commonly affected areas (with minimal collateral circulation) include the ear pinnae, paw pads, and tail 4. In this dog the pinnae and most probably tail tip were affected.

Diagnosis is based on history and clinical findings alongside compatible histopathology3,6,7. The cause of the vasculitis in this case was unknown and may have been hereditary given the familial history and lack of evidence for sepsis, drug administration or infectious disease.

There are no licensed therapies available for treatment of vasculitis. Immunosuppression is indicated for idiopathic cases when an immune mediated pathogenesis is suspected3. Glucocorticoids such as prednisolone with or without pentoxyfylline are commonly initially used1,4,5,7. Propentofylline was used in this case instead of pentoxyfylline according to the UK prescription cascade system. This drug has a similar mode of action and has been reported to be as effective in cell-poor vasculitis8. Initial steroid and Propentofylline therapy was successful in controlling the symptoms in this case. However, it was not possible to retain clinical remission at a dose of steroids that avoided unacceptable side effects.

Cyclosporine has many anti-inflammatory and immunomodulatory actions, and has been successfully used to treat a variety of immune mediated dermatoses9. There are anecdotal reports of cyclosporine use for vasculitis1,3,6,7,10, and it was therefore selected for use in this case as a steroid sparing agent. A dose of 5mg/kg daily was successful in combination with steroids to regain remission of the pinnal lesions and was well tolerated. Hypertrichosis is a known minor side effect10,11, that was addressed by increased grooming in this case. Steroids were withdrawn once the clinical lesions were controlled, and Cyclosporine in combination with Propentofylline retained clinical control of the symptoms during a 3-month follow up period.