The Use of Ciclosporin in Pododermatitis

HISTORY AND CLINICAL EXAM

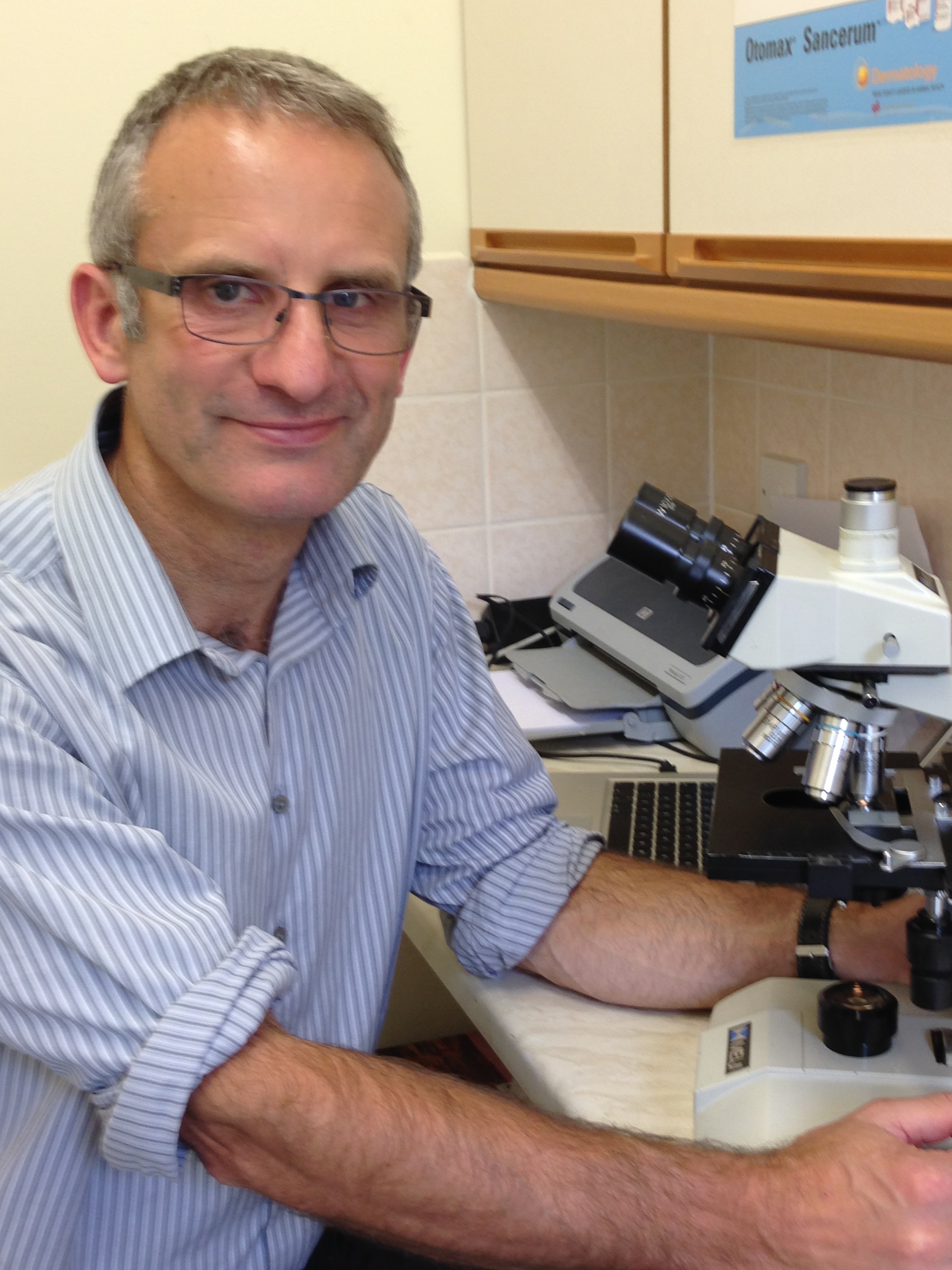

A five-year-old, neutered, male, West Highland White Terrier presented with a lifelong history of painful pododermatitis that started shortly after acquisition at two months of age. There had been a gradual progression in severity and the owner no longer took the dog hill-walking because of pain walking on rough ground.

A five-year-old, neutered, male, West Highland White Terrier presented with a lifelong history of painful pododermatitis that started shortly after acquisition at two months of age. There had been a gradual progression in severity and the owner no longer took the dog hill-walking because of pain walking on rough ground.

Lesions primarily consisted of interdigital swellings on both forefeet which would rupture and discharge haemopurulent exudate along with inflammation and swelling over the plantar aspects of the forefeet. The hind feet were unaffected. He had a tendency to lick his paws but only when inflamed; there was no other history of skin or ear disease. Skin lesions were confined to the forefeet (figure 1, 2 and 3).

General physical examination was unremarkable. There was no history suggestive of systemic involvement. An IgE ELISA environmental panel had been positive to various environmental allergens. Allergen specific immunotherapy had been started but there was no response after six months of therapy. There had been no response to a short course of glucocorticoids.

DIFFERENTIALS

-

Deep pyoderma secondary to poor foot confirmation

-

Demodicosis

-

Malassezia dermatitis

-

Atopic dermatitis

DIAGNOSTICS

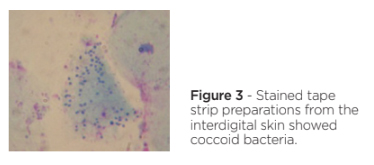

Hair plucks and skin scrapes were performed – there was no evidence of demodicosis on microscopic examination. Cytology from the draining tract showed pyogranulomatous inflammation with occasional coccoid and rod shaped bacteria and stained tape strip preparations from the interdigital skin also showed coccoid bacteria (figure 4). A swab from the draining tract was submitted for bacterial culture and sensitivity testing; Staphylococcus pseudintermedius, E.coli and Enterococcus spp. were recovered with varied sensitivities but all were susceptible to potentiated amoxicillin. A biopsy was advised for histopathological examination and tissue culture but was declined by the owner.

TREATMENT

The first stage was to treat the bacterial infection. This was a deep pyoderma so prolonged antibiotic treatment was indicated. Initial therapy consisted of potentiated amoxicillin at a dosage of 20mg/kg BID 6 weeks and daily treatment of the paws with chlorhexidine / climbazole wipes.

The first stage was to treat the bacterial infection. This was a deep pyoderma so prolonged antibiotic treatment was indicated. Initial therapy consisted of potentiated amoxicillin at a dosage of 20mg/kg BID 6 weeks and daily treatment of the paws with chlorhexidine / climbazole wipes.

During the 6-week antibiotic course there were three further episodes of interdigital swellings with draining tracts and on re-examination there was still plantar interdigital swelling. On repeated tape strip examination of the interdigital skin, no bacteria were seen on cytology. In view of the poor response to antibacterial therapy, anti-inflammatory / immunomodulatory therapy was initiated to try and reduce interdigital swelling and restore weight bearing to the footpads. Initially treatment consisted of ciclosporin 5mg/kg SID and daily applications of a potent topical glucocorticoid fluocinolone acetonide. This topical steroid was withdrawn after three weeks. Topical antiseptic therapy was continued using chlorhexidine wipes.

Three months on, there were no further episodes of interdigital abscesses, swelling or draining tracts; this was the longest period of remission for several years. There had been no adverse effects to ciclosporin use. On repeated examination, there was a marked reduction in interdigital swelling with some swelling and weight bearing on haired skin (figure 5). The dog was now able to accompany the owner on hill walks (Figure 6). Ciclosporin was continued at the same dosage.

Fourteen months on, apart from a brief relapse when treatment was switched to oclacitinib before reversion back to ciclosporin, there had been no further episodes of pododermatitis.

DISCUSSION

Pododermatitis is a complex, multifactorial condition. There are many specific diseases that can result in nail footpad or skin lesions. Similar to ear disease, various causes and factors should be considered.

The two most common primary causes of inflammation are atopic dermatitis and demodicosis. Demodicosis is important to rule out in disease affecting haired skin and easily misdiagnosed. Primary inflammatory diseases frequently lead to secondary inflammation, including pyoderma and Malassezia dermatitis. Cytology is mandatory to detect these infections. Swelling due to primary and secondary inflammation leads to perpetuating factors, such as weight bearing on haired skin, causing further damage and pain. In this case, there was no history suggestive of atopic dermatitis and no evidence of demodicosis.

The early age of onset and poor foot conformation suggested a congenital poor foot conformation with conjoined central digital pads, resulting in weight bearing on haired skin and secondary furunculosis. This progressed to a chronic inflammatory process which no longer responded to antibiotic therapy. Thus, the aim of therapy was to reduce swelling and restore weight bearing to the footpads - ciclosporin was effective in achieving this. Other options for treating this disease include systemic glucocorticoids and surgery, such as partial or complete fusion podoplasty or laser surgery to remove the proliferative tissue. These were not necessary in this case to its excellent response.

1. Breathnach, R.M., Fanning, S., Mulcahy, G., Bassett, H.F. & Jones, B.R. (2008). Canine pododermatitis and idiopathic disease, Veterinary Journal, 176(2), p146-57.

2. Duclos, D.D. (2013). Canine pododermatitis, Veterinary Clinics of North America Small Animal Practice, 43, p57-87.

3. Duclos, D.D., Hargis, A.M. & Hanley, P.W. (2008). Pathogenesis of canine interdigital palmar and plantar comedones and follicular cysts, and their response to laser surgery, Veterinary Dermatology, 19(3), p134-41.

4. Miller, W.H., Griffin, C.E., Campbell, K.L. and Muller, G.H. (2013). Parasitic skin diseases. In: Muller & Kirk's Small Animal Dermatology; 7th Edition. St Louis: Elsevier.