The Use of HCA in Pemphigus Foliaceus

HISTORY AND CLINICAL EXAM

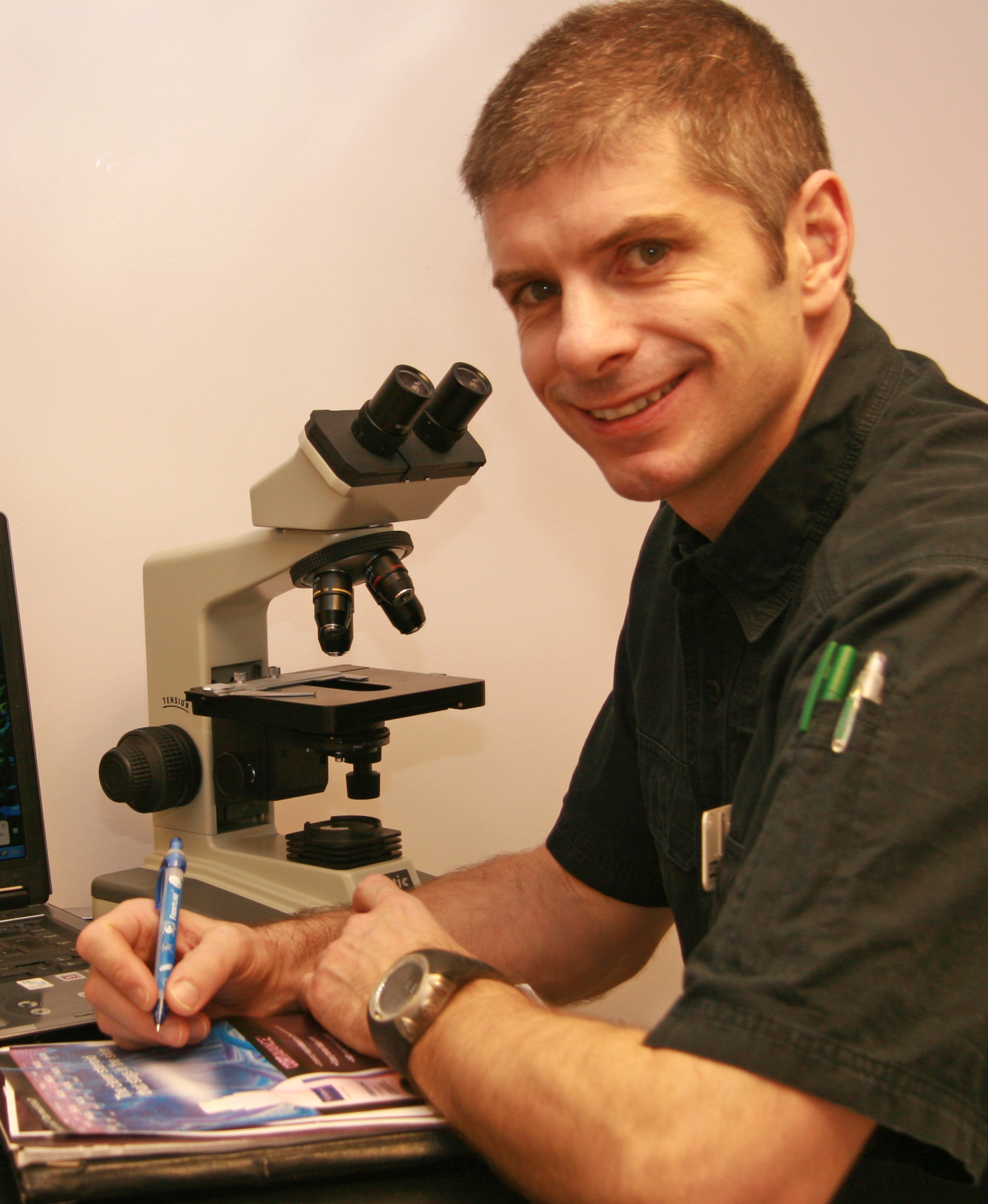

A twelve-year-old, male neutered, British Blue cat was presented with a non-pruritic, constant, progressing, multifocal dermatitis of two months duration. The lesions had not responded to two courses of oral anti-bacterials. In addition, the cat had a presumptive diagnosed of inflammatory bowel disease several years prior and subsequently was on prednisolone 1.1mg/kg PO SID for two to three years.

A twelve-year-old, male neutered, British Blue cat was presented with a non-pruritic, constant, progressing, multifocal dermatitis of two months duration. The lesions had not responded to two courses of oral anti-bacterials. In addition, the cat had a presumptive diagnosed of inflammatory bowel disease several years prior and subsequently was on prednisolone 1.1mg/kg PO SID for two to three years.

A general clinical examination was unremarkable. Dermatologically lesions were asymmetrical and confined to the head and face. There was prominent crusting and erosions on the nasal planum, external nares & right pinna. There were no other dermatological lesions (this included close examination of the oral cavity, muco-cutaneous junctions, plus the remainder of the skin, especially all pad margins, claw beds & nipples.

DIFFERENTIALS

- Auto-immune or immune-mediated diseases

- Pemphigus foliaceus (PF) – spontaneous or drug-induced

- Pemphigus erythematosus

- Systemic lupus erythematosus

- Infections

- Bacterial folliculitis – secondary or resistant bacteria

- Epidermolytic dermatophytosis

- Immunosuppression

- Iatrogenic (glucocorticoid)

- Retroviruses – FeLV, FIV

- Ectoparasitism

- Notoedres cati

DIAGNOSTICS

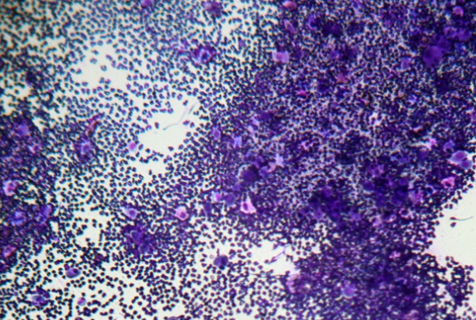

Marginal skin scrapings and crusts were examined microscopically and revealed no evidence of ectoparasites. Full haematology, comprehensive biochemistry, retrovirus screen, fructosamine assay & complete urinalysis including culture were performed; revealing no evidence of retrovirus involvement, a mild non-regenerative anaemia (likely glucocorticoid-induced), diabetes mellitus (hyperglycaema, glucosuria and elevated fructosamine), urine sediment was inactive but bacterial culture showed a heavy growth of haemolytic E. coli, sensitive to clavulanate-potentiated amoxicillin. Cytology of an impression smear taken from below the crusts revealed neutrophils and rafts of acantholytic keratinocytes; no bacteria were observed.

Multiple, small 2mm, full thickness skin biopsies plus fresh crusts were submitted to a dedicated dermato histopathologist; a provisional cytological diagnosis was confirmed of PF. Additional PAS staining ruled out epidermolytic dermatophytosis.

TREATMENT

Initial treatment consisted of:

Initial treatment consisted of:

- Exclusive feeding of veterinary gastrointestinal diet,

- Clavulanate-potentiated amoxicillin 12.5mg/kg PO BID 28d,

- Insulin SC BID (dose adjustments as required by repeat frustosamine and serial blood glucose measurement),

- Hydrocortisone aceponate 0.584% spray (HCA) topically BID on lesional areas.

Four weeks on, the UTI had resolved and there were no gastrointestinal upsets. Six weeks on, the crusting had resolved entirely from external nares & right pinna. The latter displayed some hair regrowth and well-demarcated hyperpigmentation. Focal erosions with marginal primary pustules persisted on the nasal philtral area. Six months on, the iatrogenic DM resolved. Eight months on, the localised PF disease began to generalise with additional purulent paronychia arising. The regimen was revised to:

- Continued exclusive feeding of veterinary gastrointestinal diet,

- Clavulanate-potentiated amoxicillin 12.5mg/kg PO BID 14-28d after secondary bacterial pyoderma was confirmed cytologically,

- Hydrocortisone aceponate 0.584% spray (HCA) applied topically, either as a spray or applied by cotton bud, BID-SID on lesional areas after cleansing,

- Ciclosporin 7.5mg/kg PO SID.

DISCUSSION

The majority of feline PF cases present with head and face lesions (79%) but only a few are asymmetrical (8%), as seen in this case. Prompt diagnosis and thorough assessment for concurrent and associated conditions allowed a treatment regimen to be tailored specifically for this cat.

This case showed a localised distribution of PF and glucocorticoid-induced diabetes mellitus (DM) with concurrent urinary tract infection (UTI). The initial regimen was to establish strict nutritional control, start relevant systemic antibacterials, curtail systemic glucocorticoid administration, avoid traditional immunosuppressive, potentially diabetogenic, medications and attempt to gain control of the PF with topical glucocorticoid therapy.

There are no licensed treatments for PF but traditionally immunosuppressive doses of prednisolone are prescribed for confirmed cases of feline PF, whilst other oral steroids may be used. A possible serious side effect in cats with oral steroid use is the development of diabetes mellitus. Glucocorticoids have been reported to control only 35-50% of feline PF cases adequately. In some cases, additional immunosuppression is required; oral chlorambucil, oral or injectable ciclosporin and injectable gold salt aurothiomalate may be used.

Topical treatments such as HCA, for specific cases, can:

-

allow easier management and quicker resolution, of concurrent conditions, such bacterial pyoderma or urinary tract infections

-

be employed to aid treatment compliance especially when multiple medications are required in feline patients

-

be used to avoid systemic immunosuppressive and/or diabeto-genic medications

Topical treatment with varying potencies of glucocorticoid or calcineurin inhibitors, such as tacrolimus or pimecrolimus, can be used in PF management in both humans and companion animals. HCA is one of the new class of di-ester glucocorticoids with a high therapeutic index but improved risk / benefit ratio over older traditional topical steroids.

This case presented with localised skin lesions, definitively diagnosed as PF, but in addition there was significant concurrent disease, which complicated treatment and management of this dermatopathy. Despite the challenging presentation, this case has demonstrated the efficacy of HCA as a sole treatment of localised feline PF, as well as an adjunctive treatment when it becomes generalised.