Itchy Cat? What Can Be Done?

Feline atopy is now described and the diagnosis is reached by a process of exclusion. Of course the most likely cause of a pruritic cat is a flea infestation and ensuring perfect ecto-parasite control on both the animal and the environment is essential.

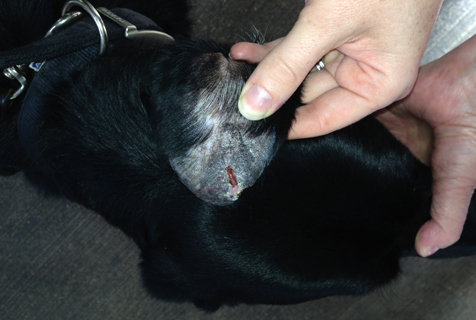

Over-grooming and self-mutilation presents with broken, barbered hairs, alopecia and redden, raised erosive plaques.

Eosinophilic invasion of these skin lesions is common and can result in the eosinophilic granulomas. The significance of the eosinophil has been questioned and the normal feline response to bacterial infections and parasites involves eosinophils. Therefore the arrival of the feline eosinophil at the skin may be more consequential to secondary infection rather than aetiological of the chronic self-mutilation.

However, some cats remain pruritic or persistent over-groomers despite all the usual causes being ruled out and religious flea treatments being applied. In these cases the first diagnostic stage is to try and identify the origin of the itch physiologically. Is it neuropathic or triggered by a pruritogen like histamine? In humans there are well described neuropathic pruritic conditions caused by both physical and psychological factors. As the itch is a subjective sensation the identification of neuropathic pruritic dermatoses in cats is very difficult indeed! Known trauma to the nerves, infectious agents like Feline Herpesvirus and stress associated behaviours can all result in obsessive self-mutilation. There are a few case studies in the literature that have used medicines ranging from anti-depressants to anti-convulsants to control the “itch”.

Allergic skin conditions in cats are common and similar to dogs there is a need for anti-inflammatories and anti-pruritic medicines. Again both topical and systemic glucocorticoids have been used but the chronic side effects are a significant issue and doses must be kept to the lowest effective dose. Treatment compliance in cats is another obstacle in successfully managing chronic dermatological conditions and cats can become very wise to the tricks used to dose them. Oral medications are not always accepted and poor palatability can cause treatment failures.

Topical glucocorticoids are well suited to many pruritic feline skin diseases and may be used to control clinical symptoms in combination with systemic medicines such as ciclosporin and prednisolone. The risk of skin atrophy and systemic absorption of topical glucocorticoids is an important factor when selecting treatments. As a potent locally acting glucocorticoid hydrocortisone aceponate was hypothesised as a treatment of choice and has been studied in cats to treat a variety of diseases including pemphigus foliaceus and eosinophilic granuloma complex. Published evidence has demonstrated efficacy in flea allergic dermatitis and whilst it is off label in cats the molecule has shown to be a valuable addition to the medical options in feline dermatology.

Another potential option for pruritic cats is ciclosporin. Oral solutions containing ciclosporin for cats are now authorised for the symptomatic treatment of chronic allergic dermatitis. Ciclosporin is a selective immunosuppressor, which makes it useful for many types of allergic skin conditions. The mode of action of ciclosporin is complex and the anti-inflammatory and anti-pruritic properties are achieved by inhibiting antigen stimulation of T-lymphocytes. The anti-pruritic mechanism has been attributed to the control of mast cell degranulation and therefore the reduction of histamine and pro-inflammatory cytokines released into tissues.

Although diagnosing pruritic cats is challenging and sometimes onerous the final results can be very satisfying when the itchy cat appears at the check-up looking content and furry with a happy owner!